Down to the last two leadership candidates, the country will now see a string of nationwide hustings for Conservative Party members, meaning an intense (and, at times, uncomfortable) summer-long debate. Like it or not, the choice of the 160,000 Tory party members will define what it means to be Conservative in 2022.

As the two candidates, former Chancellor Rishi Sunak and current Foreign Secretary Liz Truss, go head-to-head, their policy announcements to date promise to take the Party in two distinctly different directions. Who wins will determine the road ahead for Conservatism up to the general election and beyond.

Perhaps most fundamentally, the candidates differ on their approach to tax and spend, butting heads on who has the most legitimate claim to Thatcherism 2.0. Both want to create a smaller state with (eventually) lower taxes but differ on when and how to implement these. Sunak advocates fiscal responsibility, vowing to tackle inflation before making any cuts. Truss would cut taxes on day one as Prime Minister, with an Emergency Budget and new spending review paving the way, presumably, for shrinking government departments.

Without a doubt, the cost-of-living crisis will be one of the next Prime Minister’s biggest challenges, and how the candidates tackle it will likely define their premiership. With the exception of Sunak, all of the candidates in the race made commitments to do more to support people. Sunak has remained adamant that the best thing he could do to combat the cost-of-living would be to curb inflation. If he wins, he will come under huge pressure to go further.

On Brexit, neither camp will want to appear to the Party membership to be taking a soft approach towards the EU. Behind the scenes, however, the Northern Ireland Protocol is another area of key difference between the two candidates and will redefine the UK’s relationship with Europe. Sunak, after three years in the Treasury, remains alert as ever to the economic impact of policy decisions, and leans towards compromise. Truss, conversely, wants to cement her position as the hardline Brexiteer despite (or because of) voting remain in 2016.

Ultimately, this is a fight for the right of the Party. Sunak wants to distance himself from Boris Johnson’s high-spend ‘Cakeism’, while Truss seeks to woo the traditional heartland with immediate tax cuts. The challenge for both candidates, upon becoming Prime Minister, will be to unite a party that includes the European Research Group, Red Wall and One Nation Tories, and everyone in-between before the next general election.

Tax and spend

The candidates have already clashed bitterly on tax and borrowing. Sunak has branded Truss’ policy socialist, whilst she has argued that he would push the country into a recession.

Sunak insists he is a low tax Conservative. However, he will not make specific pledges to cut taxes until inflation is brought under control. In truth, he cannot plausibly pledge tax cuts now, having overseen some of the largest tax rises in recent years. He’s standing on a soapbox of fiscal responsibility, advocating low spend with future cuts on the horizon when the time is right.

Truss, on the other hand, would cut taxes on her first day in office. She has so far pledged to reverse Sunak’s increase to corporation tax and National Insurance, costing the Treasury over £30 billion. She would generate fiscal firepower by paying back the £311 billion Covid debts over a longer period – treating them akin to Second World War loans.

It is difficult to see how two political heavyweights with such opposing economic ideology could work together in a cabinet of collective responsibility. It is highly unlikely that either candidate will serve in the other’s government, instead retreating to the back benches or (in Sunak’s case if he does not win) from politics altogether. The bigger concern for the Conservative Party is whether MPs can unite around the winner to support the implementation of their fiscal policy. Whichever path is chosen, the Parliamentary Party must wholeheartedly support it if they are to stand the chance of winning the next election. If voters get any whiff of squabbling under the new leadership, the new Conservatism may end up being defined by its time on the Opposition benches.

Environment

The environment, in particular the 2050 net-zero target, had all the candidates in this race equivocating to a greater or lesser degree. Eventually, all of them pledged to support the 2050 net zero target.

While it is likely that the long-term target will remain untouched, the short-term route towards this goal looks set to be abandoned or revised, in no small part due to the cost-of-living crisis. Sunak has pledged to increase renewable production (offshore rather than onshore) and build more electric car charge points, though he has yet to announce any detailed environmental plans. As Chancellor, he largely avoided talking about net zero and some accused him of blocking green policies that had any associated spending implications.

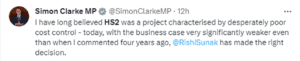

Truss committed to net-zero reasonably early in the contest, securing the backing of notable green Tories including Vicky Ford and Simon Clarke, both of whom have cited her support of Cop26 as one of their reasons for supporting her. So far though, she has pledged to ‘pause’ green levies on energy bills to save households £153 each to help ease the cost-of-living crisis. She also wants to lift the fracking ban. As Foreign Secretary she rarely bought up environmental issues in speeches or with counterparts, and as Environment Secretary she cut subsidies for solar farms calling them ‘a blight on the landscape’.

The biggest challenge for both the candidates here is that the party membership is at odds with the wider electorate on this issue. A recent poll in The Times puts the environment at the bottom of the top ten concerns of party members, and a YouGov poll found that only 4% of members believe net zero should be a priority. Contrast that with an April poll that put broader public support for net zero at 64%. It’s true that the race for leadership means the candidates have to focus on the first group, but if they want to be serious contenders in the next general election, then what?

Levelling Up

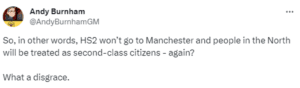

There has been a distinct lack of enthusiasm from any candidates for Johnson’s flagship ‘levelling up’ agenda. This may be a decisive move to distance themselves from his premiership, but they have not indicated what they would do for the Red Wall that won them the last election so decisively. Neither candidate wants to make commitments that would be costly to the public purse, and broadly speaking they both want to focus on reducing spending and shrinking the state.

So far, Sunak has committed to keeping a Cabinet Minister for levelling up and has promised to ensure that every part of England that wants a devolution deal gets one. He has also pledged to devolve powers on business rates to mayors and look at the devolution of post-16 education. He said he will work closely with local leaders on the future of transport investments, including Northern Powerhouse Rail.

Truss has promised to create ‘low tax zones’ across Northern England with low business rates and few planning restrictions, making it easier and quicker for developers to build on brownfield land.

Both candidates have committed to the Northern Research Group pledge card but must try harder than this to incorporate the Red Wall into their new Conservatism if they want to count these votes at the next election.

Brexit

Sunak voted Leave and his voting record has been consistently pro-Brexit. At the Conservative Party Conference last year he said “I believe the agility, flexibility and freedom provided by Brexit would be more valuable in a 21st century global economic than just proximity to a market.” He has said he will create a Brexit Delivery Department tasked with reviewing all 2,400 laws inherited from the EU. He wants to scrap and replace GDPR, overhaul laws governing the City of London, and speed up clinical trials. It is thought that he might move on the Northern Ireland Protocol and seek compromise with Brussels, though giving any suggestion of doing so at this stage in the leadership contest would be extremely high risk.

Despite voting to remain in the EU in 2016, Truss is seen, counterintuitively, as the hardline Brexiteer. She wants to reform the European Court of Human Rights but is prepared to withdraw from it if necessary. As Foreign Secretary, she introduced a Bill to unilaterally override some post-Brexit trade rules for Northern Ireland. Her supporters claim she plans to drive forward regulatory divergence from the EU, including overhauling business regulation to spur a more dynamic economy.

It’s hard to believe this is still an issue for voters six years on, but perhaps the Conservative Party will never be able to shed its complicated history with Europe. Nevertheless, the candidate that wins the leadership race will be responsible for forging a new relationship with the Continent, and how they do so in the next couple of years is likely to redefine the Party.

The missing piece?

Both candidates were participants in the outgoing incarnation of government. This should, in theory, make it a little awkward to disavow everything it has done. Although, it has seemed to trouble Truss rather less, leaving Sunak sharply and repeatedly reminding her of the notion of ‘collective responsibility’.

The candidates need not deny its achievements. But they do need to acknowledge the elephant in the room: that the leader that won them an 80-seat majority was ousted by Conservative parliamentarians less than three years later for serious and serial questions over the ethics of his Government, and of himself. Conservatives fundamentally believe in upholding the unwritten constitution and its conventions, but events of the Johnsonian era have undermined one of the central assumptions of our country’s democracy: that the Prime Minister acts as the guarantor of ethical government. In order to build a new, resilient Conservativism, they must reassure voters that this will never happen again.