How will the Whitehall machine deliver a Mission-Based government?

“We need government to be more agile, empowering, and catalytic….

“The old model of departments working in silos … needs to be replaced with a genuine joined-up approach. This means collective agreement on the government’s objectives and how best to deploy time, attention and resources to meet them.

“This could mean new structures and ways of working to facilitate collaboration, including replacing some of the cabinet committees with new delivery focused cross-cutting mission boards.”

5 Missions for a Better Britain: A Mission Government to End ‘Sticking Plaster’ Politics

A change in government is very often accompanied by a new vision for how government as a whole should be organised – from the role of No.10 and the powers of the Treasury and the Cabinet Office; to the responsibilities of the central government departments and their agencies; to the use of cross-government ‘Czars’, boards and committees.

Some of these shifts are formally called ‘machinery of government’ changes because they involve moving responsibility for functions from one department to another, or creating whole new departments devoted to goals like Net Zero. Others are changes in the balance between central and local, or in the style and way of doing things.

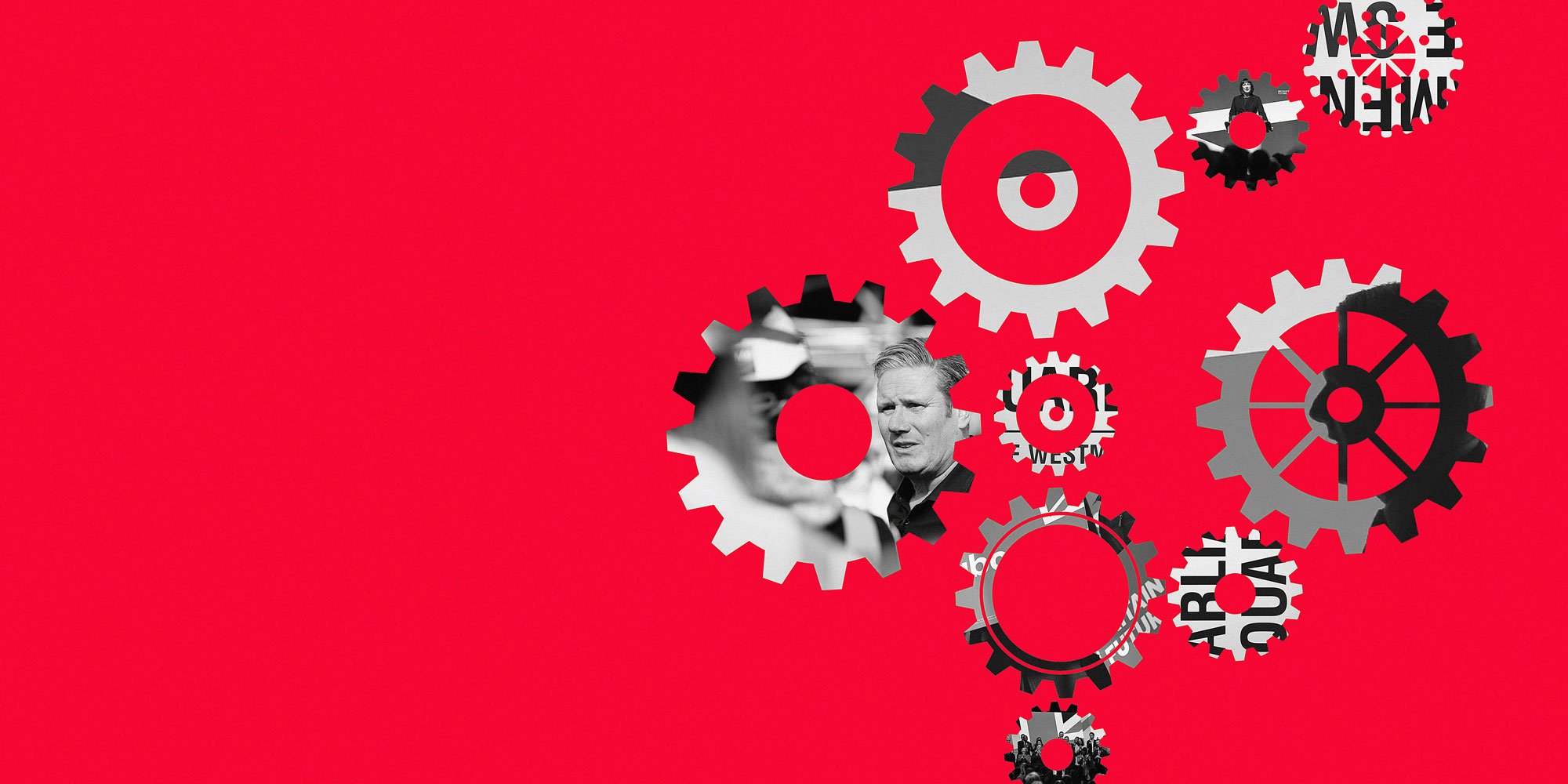

So what changes can we expect to see under a new Labour government? And how could Government really reflect Starmer’s ‘Mission’-focused government – supporting his cross-cutting ambitions around economic-growth, clean energy, an improved NHS, safer streets, and breaking down the barriers to opportunity?

In Starmer’s own words – these issues are long-term, complex challenges “that need lots of actors and agencies working to achieve them”. And of course those actors aren’t just central government policy-makers but also “business working with unions. The private sector working with the public sector. And partnership between national and local government.”

These are also issues where Labour must deliver on the promise of Change, but with little headroom for further funding increases – meaning good leadership, driving operational improvements and marginal gains become ever more important.

So, under a newly elected Labour government, it’s more likely we’ll see an emphasis on making existing structures more accountable, with stronger central control and cross-government coordination, rather than a wholesale shake-up of the structure of Whitehall.

This evolution rather than revolution also reflects the instincts of Keir’s senior team – an inner-circle heavily populated with experienced public servants. Starting with Keir himself:

- As Director of Public Prosecutions, Starmer is one of the few recent Prime Ministers to have personal experience at the very top of the civil service, working regularly with senior civil servants across Whitehall. He used to attend the weekly meetings of Permanent Secretaries when he was DPP.

- His Chief of Staff, Sue Gray, has spent decades at the Cabinet Office, right at the heart of the official machine, responsible for sensitive topics like public appointments, Ministerial conduct and government ethics. She also knows a lot about devolution and the Union having worked as the Second Permanent Secretary at the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities and having run the Department of Finance in Northern Ireland’s devolved executive.

- Or former Cabinet Office Minister and the Political Director of Tony Blair’s delivery unit, Pat McFadden – who is likely to return to the department to drive delivery of Labour’s missions. There are also several former senior Ministers in the Shadow Cabinet who bring experience of the day-to-day operation of government.

These are long-term Whitehall operators, who will have a clear view on how to control the levers of power effectively, based on personal experience – they are not Steve Hilton or Dominic Cummings figures who join government to implement ‘blue-sky’ thinking.

Here are some thoughts about what might happen in five areas:

Central Government Departments and Agencies

Sue Gray in particular will have the instinct of most senior civil servants that major changes in the number or role of departments is a distraction, and Keir Starmer will be familiar with the disruption that big organisational changes caused for other parts of government working on the affected policy areas.

Instead the focus will be on making the departments that exist more effective, and holding the Secretaries of State in charge of them to account more effectively.

In some cases this may mean central departments becoming more powerful relative to agencies – expect for example the Department of Health and Social Care to reassert some control and powers from NHS England.

The weakest departments organisationally, and probably the ones most vulnerable to change, are those that Rishi Sunak created recently in the business area – Business & Trade, and Science, Innovation & Technology.

If there are any major machinery of government changes these will be announced when Cabinet Ministers are appointed. Key decisions on cabinet committees will be made shortly afterwards – including their terms of reference, chairs and membership.

Inevitably every Prime Minister gets to a point where a refresh or a reset is required, so notwithstanding the above, machinery of government changes will not have gone away entirely under Labour: expect the option to be on the cards either later in the Parliament or the next Parliament.

HM Treasury:

We can expect an early announcement by Rachel Reeves about increasing the department’s organisational firepower – perhaps beefing up the Growth Unit function, which may also include the appointment of a new Second Permanent Secretary, a figure who can engage credibly with business (currently a big gap, especially in a department to be tasked with a greater role in galvanising business investment).

An early announcement about strengthening the role of the OBR could also be followed up by legislation, probably in the first session.

No10 / Cabinet Office:

It is less clear what Starmer and Gray will do with No10 and the Cabinet Office.

The Cabinet Office is the least loved bit of Whitehall, a sprawling mix of central functions for the Civil Service and higher-end policy coordination across domestic and security policy. No10 by contrast is a small operation which takes a different shape in each administration reflecting the personal preferences and style of the Prime Minister.

In general I’d expect Sue Gray to take a fairly traditional view of what a high-performing centre of government should look like. The shadow of Jeremy Heywood still hangs heavily over Whitehall in this way of thinking – one brilliant individual who could combine superb instincts for policy and political handling with strengths in organisational leadership and transformational drive. The trouble is that individuals like Jeremy are few and far between, and absent this kind of hero the traditional version of the centre is a long way from the strategy-setting motor of government that the modern state needs.

Expect a lot more speculation about who might succeed the current Cabinet Secretary, Simon Case, if he does move on early in 2025. A lot of this has so far been linked to the rumoured return to government of Sir Oliver Robbins – who stepped into the public limelight as Theresa May’s chief Brexit negotiator, but also held jobs in Home Office and Treasury. Other names may however also enter the frame.

Mission Boards

The much heralded centre-pieces of the new government’s administrative reforms, these will be intended to fill that central strategy-setting gap.

They may also be an important forum to draw together the range of partners, beyond central government, that ‘5 Missions for a Better Britain’ identifies as key to delivering change – for example opportunities for the private sector and corporate expertise to contribute have been heavily floated in the media, and it would be no surprise to see union and local government representation.

But the boards will struggle to be effective unless:

The objectives are tightly defined, have some realism and are not too rhetorical

One senior Minister is put in charge of each and has the power and authority to direct other colleagues/departments (as that Minister cannot always be the PM or Chancellor, you immediately get into issues of ranking / personality / rivalry)

Preferably there is one senior official responsible for driving the work of the board, with a supporting team and with budgets to match

The risk is that these boards will turn into coordinating and overseeing committees (as with many before). And that is ultimately an issue of political direction from the top, not administrative process. If they are to have real power they need to have the status of Cabinet Committees: it is possible to have non-Ministers attending Cabinet Committees but not as full members.

Local Devolution

While not a ‘Machinery of Government’ change per se, attention should also be drawn to Labour’s plans for further local devolution – where Metro Mayors are an influential part of Labour’s eco-system, and a “full fat approach to devolution” promises a further transfer of policy-making and spending powers on transport, skills, energy, and planning.

If really effective this could be the most important long-term change of all.

Watch out though for whether the Treasury concedes any ability to raise revenue – or just to spend allocations from the centre.